The science of revision

Repetitively, and cyclically testing oneself on topics that have already been covered is the most effective way to revise. But why, how and how often?

Illustrations and words

Research has shown that revising with words and pictures doubles the quality of responses by students.1 This is known as ‘dual-coding’ because it provides two ways of fetching the information from our brain. The improvement in responses was particularly apparent in students when asked to apply their knowledge to different problems. Recall, application and judgement are all specifically and carefully assessed in public examination questions.

Our own research2 has also shown that students prefer illustrations with all key concepts and that they often find themselves able to envisage the answer on a page where they had read the answer beside the image, or in relation to the image. This, they believed, helped their recall and response when they needed to answer a question under pressure.

Retrieval of information

Retrieval practice3 encourages students to come up with answers to questions. The more realistic the question is to a real examination, the better. Also, the closer the environment in which they revise is to the ‘examination environment’, the better. Students who had a test 2-7 days away did 30% better using retrieval practice than students who simply read, or repeatedly read material. Students who were expected to teach the content to someone else after their revision period did better still.4 What was found to be most interesting in other studies is that students using retrieval methods and testing for revision were also resilient to the introduction of stress. Those who simply read and re-read material suffered a 32% reduction in performance under stressful ‘exam’ conditions.5

Perception of what works and the findings

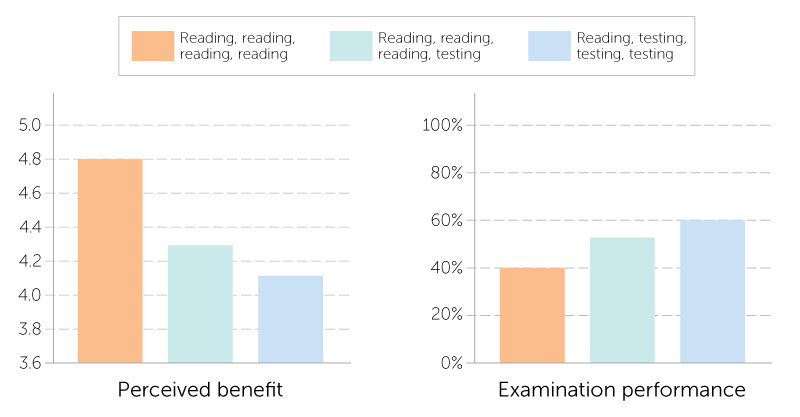

Students commonly cite reading and re-reading of material as the most common and in some cases the most beneficial revision method. They also say it is the most boring. Frequently testing themselves was far more interesting and engaging and most beneficial.3

Ebbinghaus’ forgetting curve and spaced learning

Ebbinghaus’ 140-year-old study examined the rate in which we forget things over time. The findings still hold power. However, the act of forgetting things and relearning them is what cements things into the brain.6 Spacing out revision is more effective than cramming – we knew that, but students should also know that the space between revisiting material should vary depending on how far away the examination is. A cyclical approach is required. An examination 12 months away necessitates revisiting covered material about once a month. A test in 30 days should have topics revisited every 3 days – intervals of roughly a tenth of the time available.7

At this time of year, and indeed in the longer term lead up to examinations, an evidence-based approach to revision provides a little more justification for your methods and some comfort that what you are doing is best practice.

Summary

Students: the more tests and past questions you do, in an environment as close to examination conditions as possible, the better you are likely to perform on the day. If you prefer to listen to music while you revise, songs without lyrics will be far less detrimental to your memory and retention. Silent study is most effective.8 If you choose to study with friends, choose carefully – effort is contagious.9

People also remember things better when you summarise them and write them down. Read our blog on this and how this applies to students.

https://www.pgonline.co.uk/blog/you-remember-things-better-when-you-write-them-down/?id=13

1. Mayer, R. E., & Anderson, R. B. (1991). Animations need narrations: An experimental test of dual-coding hypothesis. Journal of Education Psychology, (83)4, 484-490.

2. PG Online research, focus groups, 2020, ~184 students

3. Roediger III, H. L., & Karpicke, J.D. (2006). Test-enhanced learning: Taking memory tests improves long-term retention. Psychological Science, 17(3), 249-255.

4. Nestojko, J., Bui, D., Kornell, N. & Bjork, E. (2014). Expecting to teach enhances learning and organisation of knowledge in free recall of text passages. Memory and Cognition, 42(7), 1038-1048.

5. Smith, A. M., Floerke, V. A., & Thomas, A. K. (2016) Retrieval practice protects memory against acute stress. Science, 354(6315), 1046-1048.

6. Murre and Dros, 2015, PLoS ONE

7. Perham, N., & Currie, H. (2014). Does listening to preferred music improve comprehension performance? Applied Cognitive Psychology, 28(2), 279-284.

8. Cepeda, N. J., Vul, E., Rohrer, D., Wixted, J. T. & Pashler, H. (2008). Spacing effects in learning a temporal ridgeline of optimal retention. Psychological Science, 19(11), 1095-1102.

9. Busch, B. & Watson, E. (2019), The Science of Learning, 1st ed. Routledge.

Levels of learning

Based on the degree to which you are able to truly understand a new topic, we recommend that you work in stages. Start by reading a short explanation of something, then try and recall what you’ve just read. This has limited effect if you stop there but it aids the next stage. Question everything. Write down your own summary and then complete and mark a related exam-style question. Cover up the answers if necessary, but learn from them once you’ve seen them. Lastly, teach someone else. Explain the topic in a way that they can understand. Have a go at the different practice questions – they offer an insight into how and where marks are awarded.

≡

≡